Despite the cries of jubilation from the media following Monday’s rollout of the preliminary results from the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine study, growing numbers of scientists and economists are speaking up to reemphasize that approval of the first vaccine still remains to be seen, even as Dr. Anthony Fauci tells reporters that he expects the FDA’s emergency-use authorization to arrive in a week (having foreseen no further issues with the project, apparently).

To be sure, there’s still so much we don’t know about the quality of the vaccine, several scientists argued. And even if the approvals do arrive on schedule, there are many “known unknowns” in play, most critically, distribution, for a vaccine that may need to be administered to more than half the population to be effective.

Given the many obstacles tied to manufacturing and distribution, a vaccine – assuming the Pfizer candidate is truly effective – won’t be ready for months, according to Tai Hui, chief Asia market strategist at JPMorgan Asset Management.

There are three hurdles on the road to immunity, JPM analysts said: a vaccine needs to be approved, distributed and – and this last one is still critical – accepted.

And as we pointed out earlier, DB’s Jim Reed argued in a recent note that the process of vaccinating America, and the world, has a long way to go.

While much fuss has been raised over this “90% effective” number, even if accurate, a “90% reduction in symptomatic cases” doesn’t really tell us anything about what types of cases are being prevented, or how well the vaccine works for elderly and more vulnerable groups of patients.

The press release from Pfizer “does not at all tell us about just what they’ve actually accomplished,” said Michael Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, during a radio interview Monday on Monday.

“It’s really too early to put any definition to what this new vaccine research shows us.”

Since half the trial participants are elderly, it’s possible to project that efficacy among that group is at least 80%, according to the CEO of BioNTech, who has – or at least claims to have – little insight into the trial data. A Pfizer senior VP has said the current analysis hasn’t included any severe cases, though they’re expected to occur at some point as the trial continues. Still, while it’s looking likely that the FDA will offer some wiggle room, it’s not clear how experts reconcile the requirement that studies show at least 5 severe cases of the virus, with present expectations about the timeline to approval.

It still may be difficult to accrue the five severe cases that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has said it wants to see in vaccine trials, because the rate of serious infections has gone down as the pandemic progressed and treatment has improved, he said.

Pfizer expects to have accumulated two months of safety data for people in the trial by next week. If there are no unforeseen problems, the company could apply for an emergency use authorization in the U.S. soon after that, potentially this month.

As WSJ later points out, with 90% efficacy, roughly 70% of the population would need to receive the shot for Herd Immunity to kick in.

Plus, there’s still a formal “process” that the FDA must abide by. It has promised to be completely “transparent” about this process, partly to help assuage fears about the scramble for a vaccine potentially leading to unforeseen safety issues, or potentially harmful long-term side-effects. Already, surveys have suggested that roughly half of Americans would voluntarily get the vaccine.

Just as we saw with AstraZeneca-Oxford, and like China’s SinoVac effort is seeing now, unexpected issues could still arise over the coming weeks and months. Of course, there’s a pretty high bar, politically speaking, for any issues to disrupt or prolong the approval process since Dr. Fauci has proclaimed that he foresees no issues with the approval process. That’s far from assured.

And even once a vaccine is approved, the process of vaccinating the public could take years, as WSJ reports in a story on the many logistical hurdles facing vaccine makers. Adding another layer of risk: prior vaccination campaigns have typically focused on the young, or the elderly. Vaccinating the entire population is a much loftier goal than anything humanity has ever achieved when it comes to rapidly eradicating an infectious disease.

We should note that when we say “eradicate” we don’t actually mean make COVID-19 extinct. Although it’s certainly possible, a good number of scientists seem to think that it has unfortunately crossed the threshold to become endemic in the human population.

As states across the West, and in other areas like New Jersey, reinstate lockdown measures and other restrictions, it’s important to note that it could still be many months – possibly six months, or more – that these restrictions, or some form of restriction, will remain in effect.

David Salisbury, who previously chaired the World Health Organization’s Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization, told WSJ “is it enough to say that life will resume as usual? I think the answer is no.”

But even if the approvals continue without a hitch, lengthy supply logjams are almost inevitable. In its story, WSJ delineates the specific obstacles inherent in the supply chain for Pfizer’s vaccine.

First of all, while the federal government, via “Operation Warp Speed”, is working with McKesson to set up a distribution channel, Pfizer and BioNTech, whose vaccine candidate is, as we all learned earlier this week, the undisputed frontrunner in the race to receive that first approval, is setting up its own distribution pipeline. While Pfizer didn’t receive Operation Warp Speed money up front to help finance the project, the federal government did hand the company a cool $2 billion, a prepayment for 100 million doses, to be distributed, ideally, by January (though whether that target is met remains to be seen).

Instead, Pfizer is setting up its own operation, centered around a distribution hub in Kalamazoo, Mich. The company has turned a stretch of land the size of a football field into a staging ground outfitted with hundreds of freezers ready to take delivery of millions of doses before they can be transported to customers around the world.

From this site, and another site in Puurs, Belgium, Pfizer hopes to sell its vaccine to customers around the world.

This doesn’t seem quite as comprehensive as the plans that are being worked through in the UK, and elsewhere in Europe. In the UK, Britain’s NHS has already started running tests about shipping vaccines requiring various parameters – like extremely cold temperatures during shipment – and the EU’s leaders in Brussels have already drafted a plan regarding who should be vaccinated, in what order, starting with health-care workers, then the elderly, then essential workers.

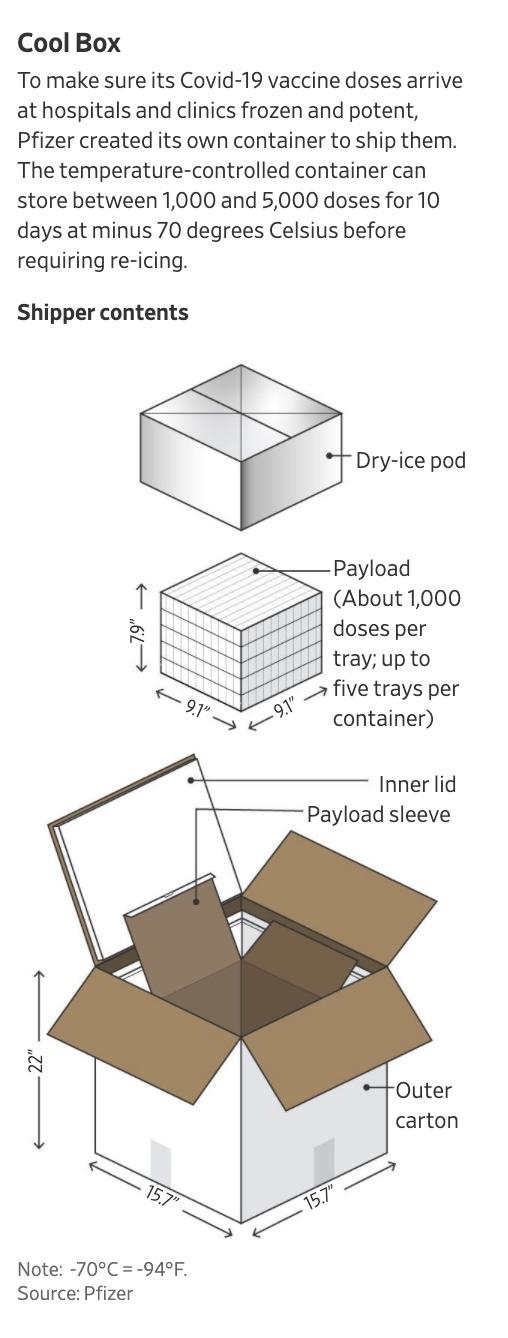

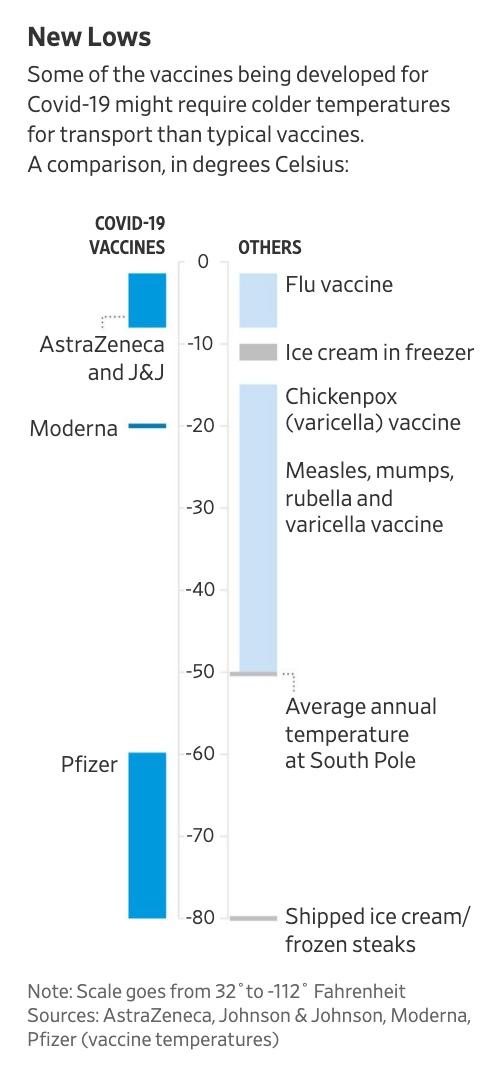

Even if the vaccine proves to be surprisingly effective, many epidemiologists have apparently told WSJ that they believe the government’s forecasts for widespread innoculation are overly optimistic. Vaccine makers are still working through strategies for shipping vaccines – some of which may need to be kept at minus 70 degrees Celsius (30 degrees colder than the temperature at the North Pole).

As a JPM analyst pointed out, companies don’t even know if there are enough freezers in the world to handle all of this.

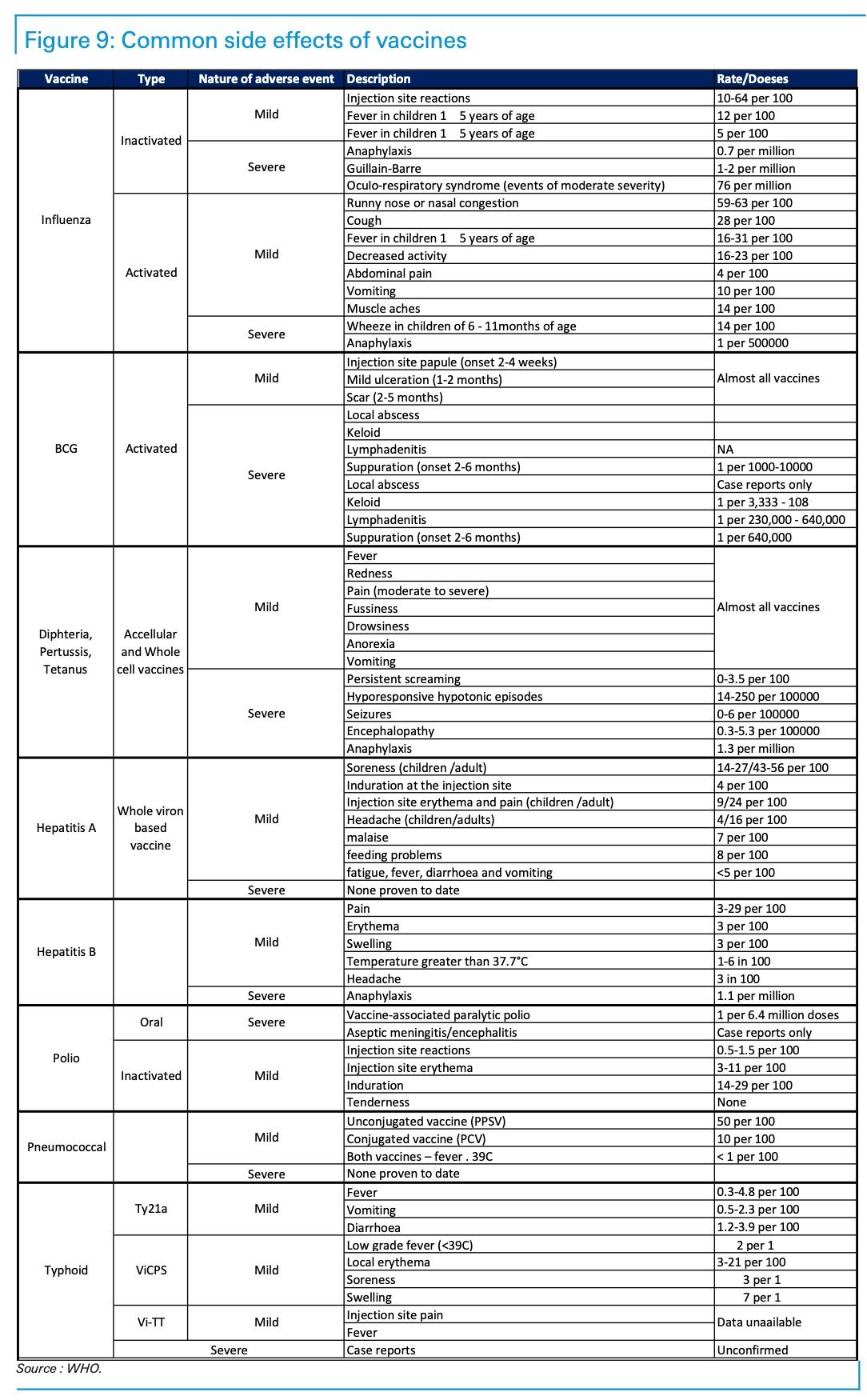

Finally, in the bank’s latest roundup on “everything we know” about a vaccine, Deutsche Bank analysts offered a rundown of all the side effects of various vaccines over the years. Side effects could stoke fears after the virus has been released, and the population is in the process of absorbing it.

Bottom line: Even Democratic politicians who purport to place “science” above all else are starting to sound notably more optimistic than actual independent scientists. With so much yet to be determined, a return to normalcy likely won’t begin until late next year. It might not even happen until 2022. And while that might seem far off now, with the Fed pressuring Congress to approve more stimulus, and Washington likely facing four years of gridlock beginning again next year, the market repercussions of this view might be priced in sooner than many traders anticipate.