By Tyler Durden

Despite $100 giveaways, offers of free hotel stays and home-delivered shots and a host of other incentives, millions of NYC residents still refuse to get the COVID vaccine. Since the reluctance and suspicion that many Americans feel about the vaccines continues to mystify the mainstream press, Bloomberg just published a story exploring the least vaccinated neighborhoods in NYC.

Ironically, many of the least vaccinated neighborhoods are the same working-class neighborhoods that were hit the hardest by the pandemic (remember how lefties screeched about minorities suffering the brunt of the pandemic while white people led the movement against lockdowns and masks?) Well, as it turns out,

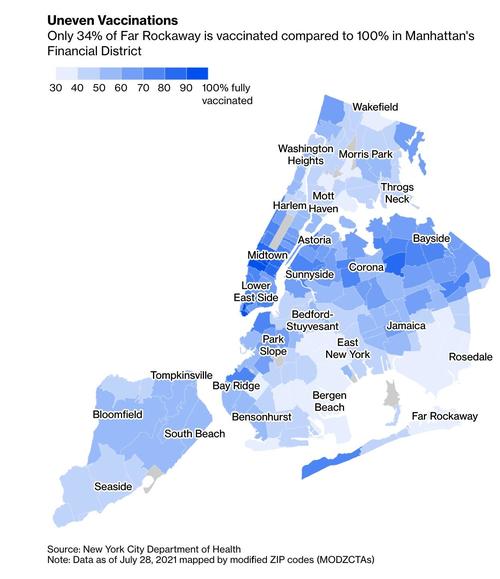

About 55% of the city’s total population is fully vaccinated. That’s roughly 400K people short of the city’s goal to fully inoculate 5MM by June. It also means more than 2MM eligible New Yorkers remain unvaccinated and vulnerable as the delta variant drives an uptick in reported cases.

While residents of the most heavily vaccinated neighborhoods (which also happen to be the wealthiest, most gentrified neighborhoods) fled to the suburbs during the worst of the pandemic, millions of residents in the low-vax neighbors lived through it all: the overwhelmed hospitals, the non-stop sirens during the spring and summer of 2020.

The biggest holdouts are mostly Black and Orthodox Jewish communities in the outer boroughs, where 17 ZIP codes have vaccination rates of 40% or less. That includes the Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Midwood, Canarsie, Ocean-Hill-Brownsville, Crown Heights and Borough Park. Participation rates have also lagged in politically conservative areas of Staten Island. In Far Rockaway, all three groups predominate. In some cases, those areas have lower vaccination rates than Mississippi.

Despite everything they have been through, they remain reluctant to accept the vaccines. For some, the motivation is religious (the Orthodox Jewish community’s resistance to vaccines helped lead to a revival of the measles before COVID made a comeback).

Source: Bloomberg

Aside from religious reasons, why are denizens of these neighborhoods so reluctant to get vaccinated? Bloomberg claims it’s a combination of mistrust, misinformation and – in some cases – access.

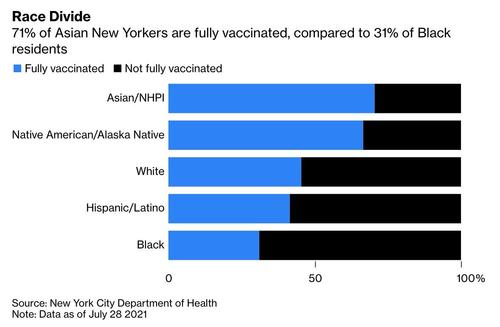

Black New Yorkers are the least vaccinated group, with a 31% participation rate. Asian New Yorkers, meanwhile, have the highest at 71%.

Among Black Americans in general, there’s a deep distrust of the government and pharmaceutical companies.

“We’re raised with the skepticism of the government when it comes to vaccines,” said Henry Butler, district manager for the community board in Bedford-Stuyvesant, which at 36% has the second lowest vaccination rate. “As Black Americans we know our history of medical exploitation and disparity of care.”

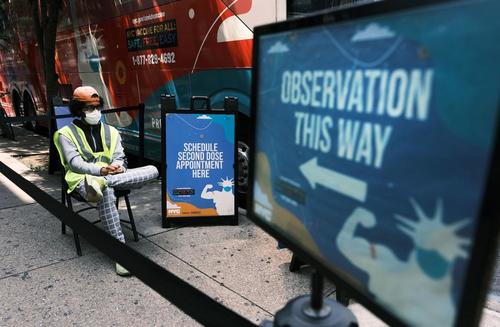

Last week, the city brought back a mobile vaccination site in the heart of Butler’s district, which according to the U.S. Census is 72% Black and 15% Hispanic.

The site gave out 39 shots last Friday, the start of the city’s $100-cash incentive — 12 more than the previous day, but only about four per hour.

“I’m not trusting the government, to be honest,” said Tony Rome, 61, one of dozens who walked past the mobile site that day. He also singled out Johnson & Johnson, which faces lawsuits alleging that its talcum powder can cause cancer. The company’s vaccine was linked to rare instances of blood clots.

“There’s not enough information about its long-lasting effects,” said Rome.

Jake Sargent, a spokesperson for J&J, said clinical trials have demonstrated “the efficacy of the J&J single-shot COVID-19 vaccine, including against viral variants that are highly prevalent” and that the results are consistent across demographics.The city has tried using trusted members of the community to promote the vaccines’ effectiveness and safety.

The Bethany Baptist Church in Bedford-Stuyvesant served as a vaccine site earlier this year, giving out 300 shots. Adolphus Lacey, the church’s pastor, said he promotes the vaccine to his congregation during Sunday services but doesn’t force the issue.

“It’s frustrating because you don’t want to insult their intelligence,” he said. “People don’t like to be shamed. I want to respect them. So you create the space for them to be honest about what they fear.”

Misinformation

At the United Methodist Center food pantry in Far Rockaway last week, Adebanji Adedipe, 64, a Nigerian immigrant, was one of two people waiting to be served lunch who said he wasn’t vaccinated. He said he’s been told the shot could cause impotence, heart failure, paralysis and mental problems.

No matter how much a health educator tried to persuade him that the vaccine is safe, Adedipe said he remained skeptical. When asked where he got his information, he said he heard it from friends. “I read it on Facebook, so I’m confused.”

In the Orthodox Jewish community, which was hit hard by the virus last year, there’s a fear that the vaccine can cause infertility, according to Alisa Minkin, a pediatrician on a Covid-19 task force organized by the Jewish Orthodox Women’s Medical Association.

Some who recovered from Covid believe they have immunity and don’t need the shot. Others are concerned about mRNA technology, the vaccine’s quick development and its emergency approval rather than full approval from the FDA.

“A lot of people in this community are very savvy,” said Minkin. “But they’re not trusting.”

To make matters worse, some Orthodox Jews felt unfairly singled out when Governor Andrew Cuomo and Mayor Bill de Blasio called out wedding parties, funerals and other gatherings held during the height of the pandemic.

“They felt very targeted,” said Minkin. “That flares up distrust even more.”

That has hindered vaccinations, said Nesha Abramson, director of community health outreach at Vaad Refuah, a community organization in Midwood, where the vaccination rate is 38%.

“We need to stop treating folks who are hesitant as ‘out there’ and nuts,” she said.

The Last Mile

Scheduling, logistics and accessibility are the other keys to reaching more New Yorkers. Sometimes it’s a matter of a mobile vaccination site sitting in the same place for more than a day. Other times, it’s ensuring that vaccine information is translated into other languages.

The city says it’s spent more than $60 million on advertising and promoting the vaccine on subways, television and radio.

Even the city’s recent $100 incentive had its hiccups. At a vaccination site at the Mosholu Library in the Bronx, an area where about 44% are fully vaccinated, some people showed up expecting cash or a gift card. They were disappointed to have to register for a pre-paid debit card online, said Nikki Edwards, a nurse who has given hundreds of shots as part of the city’s vaccine program.

“It actually discouraged people to the point where they don’t take the vaccine,” she said Saturday. “Elderly people don’t have time or sophistication to access it and young people want the money now. Several families showed up with kids as young as 12 and protested when they heard you have to be 18 to get the money.”

Still, there are signs that more people are getting on board with vaccination. On Friday, the day after the $100 incentive was announced, 14,370 New Yorkers got their first dose — the most since June 4.

For others, money won’t be the motivator. Starting Aug. 16, New Yorkers will be required to present proof of vaccination for indoor activities including dining, working out at the gym and seeing shows.

“The last miles are often the hardest,” said Chokshi. “Some people who may be a ‘no’ today will see everyone else getting vaccinated. Maybe their place of employment will require it. Maybe some of their daily activities will require proof of vaccination, and we’ll get to more and more.”