by

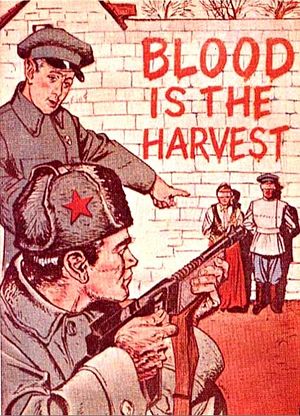

This is the third essay in my series on the history of Christianity in Russia. The first was the Bloody Baptism of Russia, covering the legendary arrival of the Apostle Andrew to the Mongol Invasion. The second covered the Mongol Yoke to the Bolshevik barbarians. This essay examines the Great Soviet Persecutions from the Revolution to the collapse of the Soviet Union.

As I headed across the cobblestone courtyard past the Sretensky Monastery towards the towering cathedral with glittering golden spires fiery and aglow in the morning sun, I couldn’t help but notice something: There were hundreds of people—many of them young people—streaming into the church. Inside the sanctuary, nearly a thousand people stood facing the priest for a service that lasted well over three hours—there was a bench along the back wall for the elderly, but most of them were far too tough to use it. I looked at it longingly about halfway through the service and got a scornful look from a wizened babushka in response.

Most of the women and girls stood on the right, and most of the men and boys stood on the left. The girls had brightly colored shawls—red, pink, blue—rosy cheeks, and shining eyes. As incense rose towards the dome and mingled with tendrils of smoke from the candles and the bearded priest’s deep voice melted into the baritones of the singers on high-placed balconies, glances shot back and forth between the girls on the right and the boys on the left, with shy smiles and nonverbal conversations exchanged. One teenage girl slipped out to meet a gangly boy in the staircase next to the sanctuary entrance, where they huddled smiling at each other with big eyes and squeezing each other’s hands until their knuckles whitened. They slipped back in before the service ended.

Those who forget just how recent the Soviet war on the churches was will not find anything exceptional about a church in the heart of Moscow packed with people on a Sunday morning. But to simply read the name of the cathedral is to be reminded: Consecrated on May 25, 2017 by Patriarch Kirill with Vladimir Putin in attendance, it is called the Church of the Resurrection of Christ and the New Martyrs and Confessors of the Russian Church. Services are presided over each Sunday by Bishop Tikhon, the man rumored to be Putin’s confessor, who helped design the church to commemorate the martyrs. The “new martyrs,” of course, are those butchered by the Bolsheviks. The church stands on the place once inhabited by a KGB headquarters where Christians and clergy were murdered.

There is still a little church from the 14nth century on the premises, as well. A little nun points us to where the iconography got painted over by the KGB, and the claw marks disfiguring the artwork. “Their hatred of Christianity and the Russian Orthodox Church was filled with rage,” she said. “Those who saw it said that the fervor reminded themselves of Dostoyevsky’s Demons.” Earlier in the week, as a friend and I ate a late supper with a historian, a filmmaker, and a journalist at the dining hall where the paperwork to end the Cold War was signed, the historian described her journeys through ruined monasteries and convents, churches with caved-in roofs, and the frenzied destruction of the artwork—paintings cut to ribbons, with sad shreds hanging from them. Similar things were done to the people.

The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 brought to power men who hated God and Christianity in all its forms. Lenin, who would end up being embalmed and put on display like a dead pope after his premature passing, once called the idea of God an “unutterable vileness.” The Russian Orthodox Church, as the chief repository of tradition and culture in Holy Mother Russia, had to be extinguished in order for the godless Soviet Union to rise from the ashes. The revolutionaries got to work as soon as they could—over 12,000 clergy were murdered outright–shot, beaten to death, hanged or drowned—and a secret 1930 police report put the number of Orthodox clergy who had died in prison camps at 42,800.

One day after taking power, the Communists passed their Decree on Land, seizing all church property and buildings on October 26, 1917. The following month, church weddings were declared invalid, along with the registration of births and funerals. In January of 1918, the Church was forced out of all the schools, and the state formally severed ties. The same month, Patriarch Tikhon pushed back, declaring the Bolsheviks anathema: “Recover your senses, madmen. Bring an end to your bloody strife. You are not merely committing the deeds of Satan, which are condemning you to Gehenna in the next world, and leave a dreadful curse upon your descendants in the present one.” The Bolsheviks responded by putting him under house arrest and ramping up their assaults—while condemnation from a despised clergyman didn’t bother them, his call to the faithful had the potential to interfere with their plans: “keep away from such monsters…The enemies of the church are trying to gain power over it and seize its property by the force of guns: resist them with the strength of your faith and join your voices in a powerful clamor of protest.”

The Bolsheviks went straight to work to silence those voices. John Kochurov, an arch-priest in St. Petersburg, was murdered on October 31. Metropolitan Vladimir of Kiev was strangled with the chain of his pectoral cross. Together with the cautionary killings of Tsar Nicholas II, his wife, the crown prince, and his four beautiful daughters in the basement of the house where they were imprisoned, it was a crimson beginning to a rising red sea of blood. As Ted Byfield noted in his High Tide and the Turn, Metropolitan Hilarion described the carnage: “Clergymen were murdered with particular brutality. They were buried alive, had cold water poured over them in sub-zero temperatures until they froze, were placed in boiling water, crucified, whipped to death and chopped with axes. Many were tortured before their deaths, or murdered along with their families or in the presence of their wives and children.”

The Bolsheviks went straight to work to silence those voices. John Kochurov, an arch-priest in St. Petersburg, was murdered on October 31. Metropolitan Vladimir of Kiev was strangled with the chain of his pectoral cross. Together with the cautionary killings of Tsar Nicholas II, his wife, the crown prince, and his four beautiful daughters in the basement of the house where they were imprisoned, it was a crimson beginning to a rising red sea of blood. As Ted Byfield noted in his High Tide and the Turn, Metropolitan Hilarion described the carnage: “Clergymen were murdered with particular brutality. They were buried alive, had cold water poured over them in sub-zero temperatures until they froze, were placed in boiling water, crucified, whipped to death and chopped with axes. Many were tortured before their deaths, or murdered along with their families or in the presence of their wives and children.”

The churches were blown up, vandalized, and smashed–many broken churches still dot the Russian countryside today. Occasional instances of outraged resistance by the faithful were often effective—at the time, the Bolsheviks preferred not to turn the people against them by opening fire. They first needed to solidify their position politically—they were already outlawing religious observance, a law that was met by another wave of defiant martyrs. Their defiance was met with force—they were shot, stabbed, and one clergyman was flung up into the air onto bayonets. In 1918 and 1919, a minimum of 28 bishops were executed along with thousands upon thousands of clergymen and laypeople.

It was not just the Russian Orthodox, either. The Bolsheviks despised all forms of Christianity, and Mennonite, Catholic, and Lutheran settlements also came under attack. Occasionally, they even banded together to fend off the marauders—for a time, lawlessness reigned, and it was open season on Christians. Interestingly, many of North America’s large and thriving Mennonite communities were originally Russian exiles fleeing this persecution—the Mennonite Central Committee (their MCC thrift stores are common sights across Canada) actually emerged from efforts to rescue their persecuted co-religionists…

READ FULL ARTICLE HERE… (thebridgehead.ca)

Home | Caravan to Midnight (zutalk.com)