by TYLER DURDEN

In our post detailing how Evergrande became a “too big to fail” anchor of China’s shadow banking system, we noted that a key missing piece in the company’s funding was selling wealth management products – i.e., unregulated “shadow banking” products – to outside investors, as well as its own employees and their families, promising returns up to 13%. It is these WMP investors that are currently besieging the company’s offices across the country in hopes of getting some of their principal back, and which include everyone from paint suppliers to decoration and construction companies. To them, Evergrande owes more than 800 billion yuan ($124 billion) due within one year, while it has only a 10th of that amount of cash on hand. It will have even less once the now officially defaulted company makes priority payments to its banks and creditors.

Expanding on this striking funding source, Reuters today writes that lured by the promise of yields as high as 12, “tens of thousands of investors bought wealth management products” through China Evergrande, a transaction which was softened by gifts such as Dyson air purifiers and Gucci bags, not to mention the guarantee of China’s top-selling developer, a guarantee which we now know was worthless.

And now, many investors fear they may never get their investments back after the cash-strapped property developer recently stopped repaying some investors and set off global alarm bells over its massive debt. Some have been protesting at Evergrande offices, refusing to accept the company’s plan to provide payment with discounted apartments, offices, stores and parking units, which it began to implement on Saturday.

“I bought from the property managers after seeing the ad in the elevator, as I trusted Evergrande for being a Fortune Global 500 company,” said the owner of an Evergrande property in the conglomerate’s home province of Guangdong surnamed Du.

“It’s immoral of Evergrande not to pay my hard-earned money back,” said the investor, who had put 650,000 yuan ($100,533) into Evergrande wealth management products (WMPs) last year at an interest rate of more than 7%. That investor is about to learn that in addition to return, there is also risk, a concept almost forgotten in today’s world where central banks and authoritarian governments do everything to preserve the “wealth effect” and avoid social unrest resulting from stock price crashes.

According to a sales manager of Evergrande Wealth, launched in 2016 as a peer-to-peer (P2) online lending platform that originally was used to fund its property project, more than 80,000 people – including employees, their families and friends as well as owners of Evergrande properties – bought WMPs that raised more than 100 billion yuan in the past five years. Of these investments, some 40 billion yuan are still outstanding, and will likely never be repaid. Last week, Evergrande revealed that even Ding Yumei, the wife of billionaire founder Hui Ka Yan, had bought $3 million of the company’s investment products in a show of support.

As the FT adds, Evergrande financial advisers marketed the products widely, including to homeowners in its apartment blocks, while its managers persuaded subordinates to invest, the executives of Evergrande’s wealth management division said.

The publication adds that one executive – who spoke during a meeting with angry investors who went to the company’s Shenzhen headquarters to try to get their money back – suggested the products were too high risk for ordinary retail investors and should not have been offered to them. Of course, it is way too late now.

“My parents put the bulk of their savings, which is Rmb200,000 and not a lot by Evergrande’s standard, into its [wealth management products],” said the daughter of one investor who asked to be identified by her surname Xu. She said an Evergrande financial adviser stationed in an apartment tower built by the company in central China had persuaded her mother to invest. “They wouldn’t have trusted Evergrande’s wealth products had they not bought the developer’s apartment,” she said. “All they wanted was to ease the financial pressure from buying expensive cancer drugs [for Xu’s mother], nothing else.”

Last week, Xu was one of hundreds of people who travelled to Evergrande’s Shenzhen headquarters in hopes of recovering their investment.

One investor named Rosy Chen and her husband, an Evergrande employee, invested Rmb100,000 this year in a product with an advertised 11.5 per cent annual return on the urging of one of his superiors. The cash went to “supplement” the working capital of a company called Hubei Gangdun Materials, according to the investment contract.

“At first we waited, but when we saw we were among the only families in the whole [Evergrande] division not to buy in, we decided to invest too,” said Chen. “We believed Evergrande wouldn’t cheat its own employees.”

Remarkably, this hit to Chinese investors and resulting social unrest, comes as a time when China’s Xi has launched a renewed pursuit of core Marxism with his “Common prosperity” initiative, which also coincides with China’s years-long effort to deleverage its economy, which has pushed companies to resort to off-balance sheet investments in search of funding. It’s why we said recently that what is happening to Evergrande is a symptom of China’s great deleveraging campaign, which however for a country with 350% debt/GDP is doomed to fail.

The funniest thing about the whole Evergrande fiasco is that it's due to China pretending it can reduce its debt without a crash.

Guys, ain't happening: at least the US accepts this and has adopted the idiocy that is MMT to justify perpetual debt increase until it all blows up pic.twitter.com/xdw4F7CTQV

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) September 20, 2021

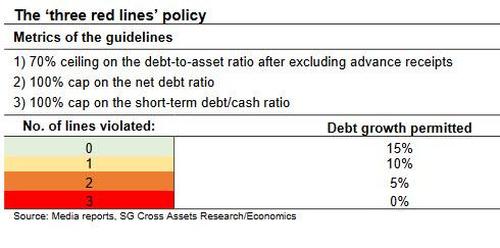

Incidentally China has only itself to blame for the Evergrande crisis. Having allowed unprecedented debt growth for much of the past decade, last year Beijing capped debt levels of property developers last year as part of its “three red lines” policy which limited how much debt growth various tiers of developers can engage in. As a result, the most indebted players like Evergrande – feeling even more pressure to find new sources of capital to ease mounting liquidity stress – ended up moving to the unregulated “shadow banking” market, and turned to employees, suppliers and clients for cash through commercial paper, trust and wealth management products.

Evergrande Wealth started to sell WMPs to individuals in 2019 after a regulatory crackdown led to a collapse of the P2P lending sector, said the sales manager and another Evergrande employee who bought the WMPs. To attract investors, the sales manager offered gifts such as Dyson air purifiers and Gucci handbags to each person who bought more than 3 million yuan of WMPs during a Christmas promotion last year.

A product leaflet provided by the sales manager seen by Reuters showed the WMPs are categorized as fixed-income products suitable for “conservative investors seeking steady returns”. It was anything but.

In an interview with local media, one Evergrande financial adviser said the products were a type of “supply chain finance”. While the money from retail investors may in years past have gone to its suppliers, the Evergrande executives in Shenzhen receiving retail investors said this was no longer the case.

Asked about Hubei Gangdun, one of the executives of Evergrande’s wealth management division said that it was just a shell company. “Proceeds from the WMPs have been used to bridge various funding gaps faced by the parent company,” the executive said. “There is no need to thoroughly examine where the money actually went.

“Some WMP proceeds were used to repay previous products but sales plummeted, making it difficult for the business model to continue,” he admitted.

“Many people . . . might be arrested for financial fraud if investors don’t get paid off,” he said. “Our products were not for everyone. But our grassroots salespeople didn’t consider this when making their sales pitches and they targeted everyone in order to meet their own sales targets.”

Translation: Evergrande used not just Ponzi instruments, but unregulated Ponzi instruments, which are now worth nothing.

In two products sold last November, a construction company in Qingdao was looking to raise up to 10 million yuan with annualized yield of 7% in one and 20 million yuan with yields ranging from 7.8% to 9.5%, depending on the investment size, in another. Minimum investments were 100,000 yuan and 300,000 yuan, respectively.

According to the sale manager, to make its products especially attractive, Evergrande offered additional yield up to 1.8% to certain investors, which would push returns to above 11% for a 12-month investment, an interest rate which in a world of zero rates, indicates funding stress if nothing else. Proceeds were to be used for Qingdao Lvye International Construction Co’s working capital, the documents showed. Repayment would either come from the issuer’s income or from Evergrande Internet Information Service (Shenzhen) Co, a subsidiary that runs Evergrande Wealth and promises to cover the principal and interest if an issuer fails to repay, the prospectus said.

The sales manager said the Qingdao company was working on Evergrande projects and would use the payment from Evergrande upon completion to repay investors.

“It’s a de-facto Evergrande product,” he said.

Other highly leveraged Chinese conglomerates including HNA Group, which declared bankruptcy early this year, and China Baoneng have used similar products. It was the overreliance of China’s giant conglomerates on shadow banking – among others – that prompted us back all the way back in 2018 to predict that after HNA and Anbang, Evergrande would fail next.

Anbang first, then HNA, Evergrande and Dalian Wanda

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) February 23, 2018

Earlier this week, Evergrande said that six senior executives would face “severe punishment” for securing early redemptions on investment products after retail investors were told that they would not be repaid on time.

Another big question is whether Evergrande ever included the 40 billion yuan of WMPs among the liabilities on its balance sheet; as the FT notes, the answer “remains unclear.”

“We expect part of it should be included in the total liabilities . . . however, there was no detailed disclosure in its financial statement, so it is difficult to verify,” said Cedric Lai, a senior credit analyst at Moody’s Investors Service.

Nigel Stevenson of GMT Research agreed it was unclear how Evergrande accounted for the WMPs. “Once the lid is lifted on its financials, it’s possible more horrors will be discovered,” he said.

In a petition to various government bodies, a group of WMP investors in Guangdong accused Evergrande of inappropriately using money that should have gone to the issuers to fund its own projects, and not sufficiently disclosing the risks. They also complained that they were misled by the stature of its chairman, Hui Ka-yan, noting that he was seated prominently during a 2019 celebration of the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China.

“The investors trusted Evergrande and bought Evergrande’s WMPs out of our love for and faith in the Party and government,” they wrote.